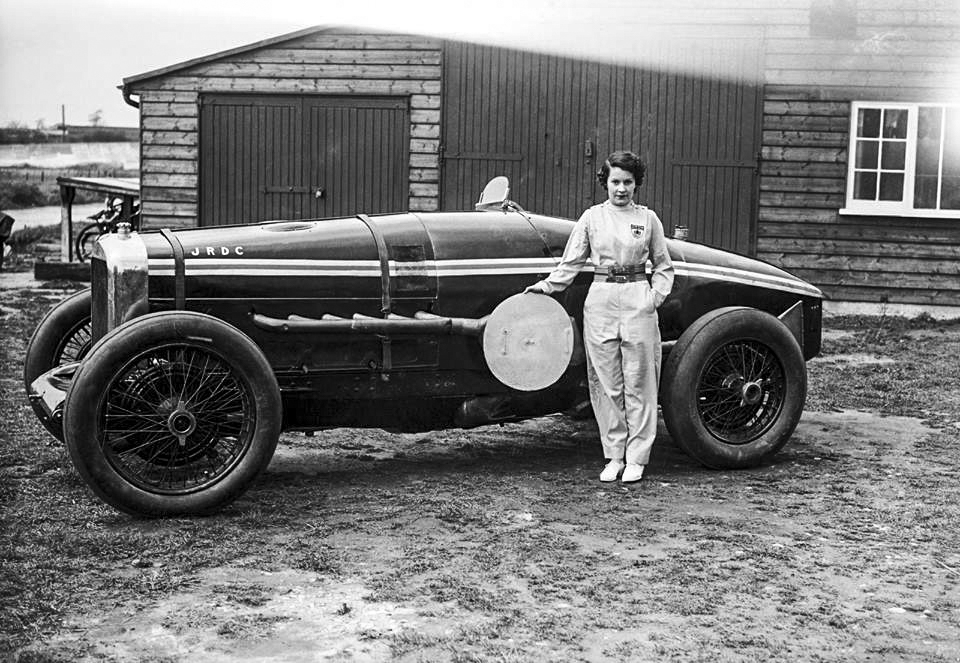

Lapping Brooklands at 134.24mph in 1935 in the ten and a half-litre V12 Delage, secured Kay Petre as one of the fastest ladies on the racing circuit. The Delage had been specially adapted for her for as her regular race car, by extending the pedals and installing a raised seat in order for to see better for her slight 4 foot, 10 inches in height. And a special car it was: the 1924 Land Speed record breaker, which did 143mph on the Arpajon road near Paris.

So, who was Kay Petre and how did she get to become the fastest woman of her time?

Kay Defries was born in 1903 into a successful family in Toronto, spending her later school days in England and studying Art in Paris. Kay Defries returned to Canada in her early twenties and got married. She became a prolific ice-skating champion, but soon after her husband passed away. She met her second husband, the retired RAF ‘Military Cross’ officer Henry Petre of Ingatestone Hall, in Essex whilst he was on a business trip in Toronto. He brought her back to England and shocked everyone by marrying her, across the threshold of the Brooklands Flying Club in 1929. The shock being that his nickname was “Peter the Monk” from his vows of celibacy! It seems however that this love affair was to last, and it was Petre who introduced Kay to racing cars.

So, let’s begin with some of the cars Kay raced. Always dressed in pale blue overalls, Kay started in a little Red Wolsley Hornet Daytona, after toying with Henry’s Invicta. She won the Ladies Race at Brooklands in the Hornet and progressed swiftly to a two and a half-litre supercharged Type 35C Bugatti, in which she achieved her first Brooklands lap record in 1934 at 124mph; she set another record in 1935 with the Delage at 134.24mph.

So, let’s begin with some of the cars Kay raced. Always dressed in pale blue overalls, Kay started in a little Red Wolsley Hornet Daytona, after toying with Henry’s Invicta. She won the Ladies Race at Brooklands in the Hornet and progressed swiftly to a two and a half-litre supercharged Type 35C Bugatti, in which she achieved her first Brooklands lap record in 1934 at 124mph; she set another record in 1935 with the Delage at 134.24mph.

Kay painted all her cars to match her overalls, and kept in a small compartment behind the seat, lipstick in a case, a stopwatch, cigarettes, hair pins and various beauty supplies to ensure one was transformed back to perfection, after completing a race. Cars built prior to 1934 had no such special place for delicate items despite the number of women racing. It was Kay’s upgrades to each of her cars that started her fascination for utility and design, and to this day I always call what we now know to be the Glove Compartment as the ‘Kay Petre Glove Compartment’!

Although Kay won many solo races, she partnered up with Dorothy Champney (who later became Mrs Victor Riley) in a Riley works car for the 1934 Le Mans 24 Hours. With Dorothy particularly good at trials, Kay and Dorothy made a concerted effort to get to know the eight mile circuit. Despite finishing in eleventh place (averaging more 60mph for the full 24hour race) they had won the coveted Rudge-Whitworth Cup finishing with all the six Riley teams cars intact. The first of the Frenchwomen, Anne Cecile Itier, finished 17th in an MG.

Although Kay won many solo races, she partnered up with Dorothy Champney (who later became Mrs Victor Riley) in a Riley works car for the 1934 Le Mans 24 Hours. With Dorothy particularly good at trials, Kay and Dorothy made a concerted effort to get to know the eight mile circuit. Despite finishing in eleventh place (averaging more 60mph for the full 24hour race) they had won the coveted Rudge-Whitworth Cup finishing with all the six Riley teams cars intact. The first of the Frenchwomen, Anne Cecile Itier, finished 17th in an MG.

The 1934 Le Mans 24hour race was quite a different beast to how we know it to be today. Two drivers would race for around three hours each, carrying on board very minimal spares, as the driver would have to do all the repairs if trouble occurred outside of the pitlane, with one mechanic waiting for them there. With this in mind, our ladies needed to know the nuts and bolts of their cars in order to race at the infamous 24 hour event.

The next year, once again in the Riley, Kay partnered this time with Elsie “Bill” Wisdom, retiring on lap 38 with a blown engine bearing. An exciting year though, for women racing drivers at Le Mans in 1935, as George Eyston, then a star of the racing and land speed records, set up a 3 car MG PA Midget Works Ladies team with the cream of the crop from Brooklands and European road races, with Margaret Allen and Coleen Eaton in car no.54, Doreen Evans and Barbara Skinner in car no.55, along with Joan Richmond and Eveline Gordon-Simpson in car no.56. The MG Works team was known as “The Dancing Daughters”. The race was an enormous success (thankfully to Eyston who had put his reputation on the line for MG), with simply lightbulb changes required to the Doreen Evans’ car.

The next year, once again in the Riley, Kay partnered this time with Elsie “Bill” Wisdom, retiring on lap 38 with a blown engine bearing. An exciting year though, for women racing drivers at Le Mans in 1935, as George Eyston, then a star of the racing and land speed records, set up a 3 car MG PA Midget Works Ladies team with the cream of the crop from Brooklands and European road races, with Margaret Allen and Coleen Eaton in car no.54, Doreen Evans and Barbara Skinner in car no.55, along with Joan Richmond and Eveline Gordon-Simpson in car no.56. The MG Works team was known as “The Dancing Daughters”. The race was an enormous success (thankfully to Eyston who had put his reputation on the line for MG), with simply lightbulb changes required to the Doreen Evans’ car.

Ladies made a regular presence at the Le Mans race-track, with Marjorie Eccles in 1937 in a Singer Nine, with Freddie de Clifford; they did not finish, whilst Dorothy Stanley-Turner, driving an MG Midget PB with Enid Riddell did, in sixteenth place. We return to 1934 at Shelsley Walsh Hill Climb where, on the 9th of June 1934, with Joan Richmond third in class, Kay Petre with her Bugatti Type 35 achieved the Hill Climb ladies’ record. She did this once more in 1937 in her single-seater Austin at 43.8 seconds (the record currently held by Nicola Menzies Gould in a 3500cc GR55, with 24.70 seconds, 2021).

This 1935 season however, for Kay Petre was her best, with the Delage, lapping at 134.24mph Kay went on to win her very first handicap race on the Brooklands outer circuit in the Bugatti at 118mph, then purchased a white one and half-litre Riley and resprayed in her favourite colour, the pale blue of her overalls. A super purchase as she took 3rd place in the Brooklands Mountain race and broke another class record at 77.97 mph.

This 1935 season however, for Kay Petre was her best, with the Delage, lapping at 134.24mph Kay went on to win her very first handicap race on the Brooklands outer circuit in the Bugatti at 118mph, then purchased a white one and half-litre Riley and resprayed in her favourite colour, the pale blue of her overalls. A super purchase as she took 3rd place in the Brooklands Mountain race and broke another class record at 77.97 mph.

However, It was the competition between Gwenda Stewart and Kay Petre that most people were interested in that year. Gwenda Stewart, who drove a 1600cc Derby-Miller, came straight from racing in Paris, where she had become the fastest woman round the Montlhery Circuit in the car that had the outright record at the same circuit; she was the contender for the Outer Lap Record at Brooklands. The Land Speed Record ten and a half-litre V12 Delage of Kay Petre’s was equally the focal point of the conversation. The officials thought that allowing two women to race each other would court disaster (if you can remember that previously officials thought Camille Du Ghast had too much “female excitability”). They decided that the two ladies would do three timed circuits of the track, and the one recording the fastest lap would be the winner.

With the women agreeing and the crowd in suspense, Kay reaching speeds of 129.03, 134.24 and 132.88mph, with Gwenda reaching 133.67mph before her car had to be brought in slowly. The next day she went out again and reached 135.95mph. Only nine drivers had ever attained such speeds on the circuit, and both ladies were the only women to be awarded the BARC 130mph badges. Many news correspondents at the time said that if they were both allowed to race against each other, Kay Petre would have won outright.

With the women agreeing and the crowd in suspense, Kay reaching speeds of 129.03, 134.24 and 132.88mph, with Gwenda reaching 133.67mph before her car had to be brought in slowly. The next day she went out again and reached 135.95mph. Only nine drivers had ever attained such speeds on the circuit, and both ladies were the only women to be awarded the BARC 130mph badges. Many news correspondents at the time said that if they were both allowed to race against each other, Kay Petre would have won outright.

Kay was happy racing a number of cars, along with her own Riley, although after entering the International Trophy at Brooklands, a simulated endurance race in an ERA, the car suffered from misfires and finally spun in the chicane. Running back to the pits covered in sand, she had a dislike for ERA’s from then on.

In 1937 Petre travelled to South Africa for the Grand Prix motor racing season with her one and a half-litre Riley, but with the lack of correct fuel arriving on time, she finished eleventh. Despite the poor result, Kay met Bernard Rosemeyer at the race who was racing for Auto Union, and who let her drive the six-litre Grand Prix Auto Union, with Mrs Rosemayer being the only woman allowed to drive it previously.

Petre raced many times at Donington Park, a circuit that was almost like road racing on private land. Measuring just two miles round, the drivers found it difficult due to its many different corners. In one of her 1936 races, an oil line broke on her Riley, showering her with hot oil. After making her way back to the pits, borrowing a topcoat and towel from Marjorie Eccles she disappeared to the back of the pits and found a clean pair of overalls, whilst her mechanics were making the necessary repairs. To the delight of the spectators, Kay Petre roared back out into the race looking pristine as ever (in an oversized pair of overalls), making up for lost time.

Although in personal correspondence Kay said that she was happiest racing with Austin in 1937, with drivers and mechanics being “absolutely first class”, it was to be this year when her career ended terribly.

Kay was driving car no.3 at Brooklands for the works Austin team during a practice for the 500-kilometre race when driver Reg Parnell lost speed, slid down the banking and hit her Austin Seven from behind, causing her to crash at 90mph and be seriously injured. Kay never raced professionally again, although she did take part in the Alpine cup and Monte Carlo Rally with Joan Richmond. She took to journalism, first as a food writer and then a motoring correspondent for the Daily Sketch magazine. Kay became the first woman to join the Guild of Motoring Writers.

Kay was driving car no.3 at Brooklands for the works Austin team during a practice for the 500-kilometre race when driver Reg Parnell lost speed, slid down the banking and hit her Austin Seven from behind, causing her to crash at 90mph and be seriously injured. Kay never raced professionally again, although she did take part in the Alpine cup and Monte Carlo Rally with Joan Richmond. She took to journalism, first as a food writer and then a motoring correspondent for the Daily Sketch magazine. Kay became the first woman to join the Guild of Motoring Writers.

Throughout her racing career, Kay was very much a hands-on person, ensuring the car was tweaked as much as possible and in line with her style, always turned out to the circuits with a chic finesse. It is not surprising then in the 1950’s Austin employed her as their colourist for the new A40 Cambridge models (many older of readers may remember the pale blue colourways of the Austin models). Later employed at the British Motor Corporation to make cars appealing to women, Petre went on to design the interior patterns for the 1970’s Mini.

After her husband Henry Petre died in 1962, she lived alone in St John’s Wood, London, then in Parkwood House care home in Camden, where she died on 10 August 1994 at the age of ninety one.

If only I knew in the 1990’s about these amazing women I have so come to admire, I would sit with Kay for hours asking questions and recording her motor racing world. I still have so many questions for you Kay, and will endeavour to keep on researching your life and all those ladies you raced alongside.

Next time I write about my favourite of them all, the Honourable Mrs Victor Bruce.

Until then,

Lara