The year is 1965 and we are at the Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah. The sun is bright with a thin layer of heat hovering above the crystal ground as the Green Monster Cyclops Jet car reaches the speed of 315.74mph. The driver is Betty Skelton, the First Lady of Firsts.

In this edition for the Women in Motorsport Series, I would like to introduce you to Betty Skelton Frankman Erde, born in June 1926, with her family home under the flight path of the local Naval air station in Florida, USA. Her toys were aeroplanes rather than dolls and she read everything on aviation: her parents realised she was serious about flying. A Navy ensign took interest in the Skeltons, so they had flying tuition together. By the time Betty was twelve she was flying solo in his Taylor Craft aeroplane. Her father also continued his interest in flying with his own aviation tuition company, and at the age of sixteen Betty received her Civil Aviation Authority private pilot’s license and qualified for the Women Airforce Service Pilots program. However, the permitted age for the WASPS was eighteen, so Betty had to wait to be productive in the program.

The young Skelton worked at Eastern Airlines at night and rented planes in the day to increase her hours. At eighteen she received her commercial pilot’s license and qualified for a flying instructor, joining the Civil Air Patrol in 1941.

The young Skelton worked at Eastern Airlines at night and rented planes in the day to increase her hours. At eighteen she received her commercial pilot’s license and qualified for a flying instructor, joining the Civil Air Patrol in 1941.

I recently listened to an interview with Betty Skelton in 1999, from the Nasa Oral History Archives (don’t worry, we shall get on to that part of her life shortly!) and I think Betty explains it best,

‘Well, by this time we were in Tampa, Florida. My dad had a flight operation there. They were having a local air show and somebody at the meeting said, “Why don’t we have that little girl out at the airport do some aerobatics.” And my dad was there and he said, “She doesn’t know how.” And another man who was there, Clem Whittenbeck, who was a great aerobatic pilot in the thirties—I’m talking about back in the forties now—he said, “Oh, I’ll teach her how.” with only a couple of weeks left until show time, he taught me how to do one loop and one slow roll.

‘The day of the show, I flew so high to be incredibly careful, that I didn’t believe anybody could see me at all, but when I landed, a man who owned an airport not very far away came up and said, “We’re having a show pretty soon. How much would you charge to come fly in our show?” And that’s when I became a professional aerobatic pilot, quite by accident.”

Betty started working in air shows in a 1929 model Great Lakes airplane, a 2T1A. She met a man named Curtis Pitts, who designed aeroplanes, and was endeavouring to design a new model at that time. Betty fell in love with it, but it was only the second plane Pitts had ever designed and the only one he had built so far, so he was reluctant initially to let her acquire it. Eventually, he gave in and let her have the plane.

Betty started working in air shows in a 1929 model Great Lakes airplane, a 2T1A. She met a man named Curtis Pitts, who designed aeroplanes, and was endeavouring to design a new model at that time. Betty fell in love with it, but it was only the second plane Pitts had ever designed and the only one he had built so far, so he was reluctant initially to let her acquire it. Eventually, he gave in and let her have the plane.

Skelton later flew in air shows with the Navy team, the Blue Angels.

“I think the thing I enjoyed most,” Skelton recalls in the Nasa Oral History interview, “and yet was probably one of the most dangerous, was flying upside down about ten feet above the ground, cutting a ribbon with the prop of the aeroplane. If nothing else, if nothing else gives you a thrill, that will, I’ll tell you!”

Skelton went on to say, “I was selected to represent the United States one year in the London Daily Express Air Pageant at Gatwick Airport. And knowing all of the Air Force guys and the Navy guys from air shows, I had an opportunity to try to land my little Pitts Special which only weighed 540 pounds on a carrier. Of course, that was unheard of, for a woman to go on a carrier. So, I took it over with me on the Queen Mary, flew in England, and then flew it across the Irish Sea and was a guest of the RAF in Ireland, and flew there.”

Skelton went on to say, “I was selected to represent the United States one year in the London Daily Express Air Pageant at Gatwick Airport. And knowing all of the Air Force guys and the Navy guys from air shows, I had an opportunity to try to land my little Pitts Special which only weighed 540 pounds on a carrier. Of course, that was unheard of, for a woman to go on a carrier. So, I took it over with me on the Queen Mary, flew in England, and then flew it across the Irish Sea and was a guest of the RAF in Ireland, and flew there.”

In 1949, Skelton set the world light-plane altitude record of 25,763 feet in a Piper Cub. She broke her own altitude record two years later with a flight of 29,050 feet. She held the world speed record for a piston-engine aircraft at 421.6mph in a P-51 Mustang racing plane. Betty was US Female Aerobatic Champion in 1948, 1949, and 1950. Her last two championships made her and her plane, Little Stinker, famous; she retired from aerobatics and sold the plane in 1951. The plane now resides with the Smithsonian museum.

Betty continued her commercial aviation work, and flew a charter flight for Bill France Sr., who then was just getting NASCAR started. She flew him and three of the drivers to a race in Pennsylvania, and on the way back Bill France piped up, “How would you like to come down to Daytona for NASCAR Speed Week?”

Very easily, Betty got behind the wheel at Daytona Beach and became the pace car driver. A Dodge sedan was clocked for her first run on the beach sand at 105.88mph, setting a stock-car speed record for women. She went on to break her own records on 3 consecutive runs. Betty recalls in her interview that she drove on the sands of Daytona ‘long before the track was built’, and doing ‘a run with NASCAR in a ’56 Corvette. I think the (average) speed was somewhere around 143, 144 miles an hour.’

Very easily, Betty got behind the wheel at Daytona Beach and became the pace car driver. A Dodge sedan was clocked for her first run on the beach sand at 105.88mph, setting a stock-car speed record for women. She went on to break her own records on 3 consecutive runs. Betty recalls in her interview that she drove on the sands of Daytona ‘long before the track was built’, and doing ‘a run with NASCAR in a ’56 Corvette. I think the (average) speed was somewhere around 143, 144 miles an hour.’

Betty broke the record for the last time at 156.99mph in 1956, on the newly constructed road course. It was only natural then that more records were there to be broken, and this led to her being the first woman to drive a jet car over 300mph at the Bonneville Salt Flats.

Betty recalls,

’Art Arfons, bless his heart, wonderful man, who had the Green Monster at that time, Art said, “Well, you can drive my little Green Monster Cyclops,” which was really an open cockpit drag racer, and they weren’t made for the type of thing I was trying to do with it. But we took it out to Bonneville and Art let me drive it. My top speed on the last run, I think, was over 315 miles an hour. I was the first woman to go over 300, and so forth. Art was simply scared to death, and I was just busy. I was really busy. The car got airborne with me towards the end of the run, and a great, great compliment to Art, because the car was easy to handle and I got it back on the ground, fortunately going the same direction it was going when it took off, and I appreciated his engineering ability in building a very stable car. It was quite an experience.’

Betty was such a spirit and worked on the advertising department for Chevrolet, which in fact is how she met her husband who was working for with the Ford agency at one time.

Betty was such a spirit and worked on the advertising department for Chevrolet, which in fact is how she met her husband who was working for with the Ford agency at one time.

“(We were) bitter rivals and didn’t particularly like each other very much,” she laughs in her interview, “but we smoothed that out. It’s the finest thing that ever happened to me, really, by far the most rewarding and the finest.”

And here is where the interview with Betty comes into its own: how did she start working with Nasa?

“One morning I picked up the newspaper and there was a picture of seven people, they had announced the day before that they were selected as astronauts. This was in April of 1959. I thought, “Wow! Wouldn’t that be wonderful to be one of these people.” But I knew at that time that women were not considered in that category and had not been considered and probably would not be for a long, long time. And, of course, I realized this from my past experiences in flying in air shows.”

The requirement to be part of the Mercury Astronauts was to have had 1,500 hours of jet flying time, but women were not allowed to fly jets in 1959. So, Betty’s chances of becoming an Astronaut were impossible. However, three months later she received a call saying that NASA had agreed to let a woman for the first time take some of the astronaut tests they had given the original seven astronauts. Due to her background and experience in flying and the thousands of hours that she had, they wondered if she would like to do it.

The requirement to be part of the Mercury Astronauts was to have had 1,500 hours of jet flying time, but women were not allowed to fly jets in 1959. So, Betty’s chances of becoming an Astronaut were impossible. However, three months later she received a call saying that NASA had agreed to let a woman for the first time take some of the astronaut tests they had given the original seven astronauts. Due to her background and experience in flying and the thousands of hours that she had, they wondered if she would like to do it.

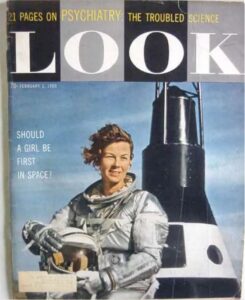

In the little time she spent there working with the NASA test and the astronauts, Betty did everything she could. to try to convince them that a woman could do this type of thing and do it well. The whole experience was published in LOOK magazine, and caused a stir amongst women pilots which started the push for women astronauts. Valentina Tereshkova was the first Russian woman Astronaut in 1963, and in 1983 Sally Ride was the first American woman to go to space. It wasn’t until 1999, forty years later, that a female astronaut would venture to space in a commanding role: Eileen Collins was the first woman to command a Space Shuttle, taking Columbia into Earth orbit to deploy the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

Back in 1959, after she had worked with the Mercury 7 astronauts and NASA, Betty went back to work with Chevrolet as one of the first women to work within the advertising industry as an influential part of the company, when at that time women were restricted to clerks and more menial tasks. She also continued flying, perhaps less ardently, with her dog Tinker joining her for trips.

“He’d sit in my lap most of the time or on the back of my shoulder, and had its own little parachute.”

Betty told a story to the Nasa Oral History project about delivering a P-51 plane back to its owner after an aeronautical display.

“Oh, I delivered the plane back safely with my coveralls over the outside, very loose, and before I got out of the airplane, I would unzip and throw the coverall off, and I would get out in a dress and have my shoes handy, my heels, to put on, because I felt women should create a nice and good impression of women who do what most consider masculine things. And I’ve always felt that way. I think it’s very important that no matter what you’re doing, you remain a lady.”

Betty Skelton set numerous firsts for women in aviation, land, space exploration and advertising. I wonder what she would make of all the space exploration after her death in August 2011? What was it that made this remarkable woman strive for these distinctions?

Betty Skelton set numerous firsts for women in aviation, land, space exploration and advertising. I wonder what she would make of all the space exploration after her death in August 2011? What was it that made this remarkable woman strive for these distinctions?

“My heart makes me tick,” she concludes in the Nasa interview, “and it’s my heart that makes me do these things, what I feel inside. As Sir Edmund Hillary said, he climbed Mount Everest because it was there. I don’t think I have any better answer than that, except that everyone is built a little differently, and my heart and my will and my desires are mixed up with challenge.”

Next time, I would love to share with you the life of Pat Moss.

Until then,

Lara

x